Frigiliana

It was the last morning of our stay in Spain.

We packed up, tidied our little apartment, loaded up the Mini (we’d let the rental agency talk us into the upgrade), and headed north up from the outskirts of Nerja to the village of Frigiliana.

The trip had been one of highs and lows. There had been blissful hours spent floating in the Mediterranean, sipping sangria in a beachside bar, exploring the sublime, surreal geometry of Alhambra. We’d also managed to spend a few lost and quarrelling in the labyrinthine streets of Granada or blearily debating tapas protocol in front of impatient Spanish waitstaff, hungry, irritable and up way past our bedtime.

Fortunately, Spain is too full of fascinations to easily spoil. The balance of the trip was positive. To tip it into ‘great adventure’ territory, we both knew it was important to end on a high note.

So up we went.

The 3.5 mile drive from Nerja to the village of Frigiliana is like a gondola ride, a swift ascent through terraced groves of mango, avocado and olive trees, climbing almost 1,000 feet to a heady, panoramic precipice of cobblestone streets and white-washed houses.

The chocolatier Levi Angelo’s was the only restaurant open in the quiet Plaza de Tres Culturas on this bright Tuesday morning. Chocolate for breakfast was a thing in Spain, I had been reliably informed by Google, and I was ready to embrace tradition. Alongside standard cafe fare, the menu I had perused online offered drinks with names like Framboise Dragon (dark chocolate with raspberry and tarragon) and Spicy Theobroma (dark chocolate and pepper, anise and cardamom), homemade chocolate hazelnut spread and pain au chocolat (naturally).

It was the off season. The streets were unpeopled, the air was cool and clear, and the vista stretched out from the steep green walls of the Sierra across the glittering Mediterranean. We sat in perfect peace, sipping spiced chocolate, surrounded by the sea and the sky, both so blue there was almost no horizon between them.

Frigiliana today is a postcard-ready tourist’s vision of Spain, having won multiple awards with titles like ‘Andalucia’s prettiest village.’ It appears on list after list of must-see places for those who want to experience ‘the real Spain,’ or ‘travel back in time.’ It seems the obvious foil to the mercilessly commercialized, British-holidaymaker-ravaged time-share farms of neighboring towns like Málaga. And it couldn’t be denied, as we later followed the narrow, cobbled alleys up into the Barrio Alto, the famously well-preserved Moorish quarter of the village, the winding nooks and crannies full of arched doorways, the blooming vines spilling over wrought iron balconies, the brilliant whitewashed houses with their red slate roofs, all this was much closer to what I had imagined when my parents described the Andalucia in which they had lived forty-five years before.

The truth, as with everything in Spain, is more complex.

Frigiliana’s true history spans almost 3,000 years of conquest and overthrow, plague and poverty, rebellion and reprisal. The Phoenicians came, then the Romans, who were sacked by the Vandals. The Moors built a castle at the top of town, which was destroyed in dramatic fashion by the Catholic kings in 1569. Within living memory, the Spanish Civil War devastated the town over decades. Though the war officially ended in 1939, brutal repression and partisan fighting continued for another 20 years throughout the inaccessible, porous peaks and caverns of the surrounding Sierra Almijara. The town was left exhausted, traumatized and, according to one historian, in “almost medieval levels of poverty.”

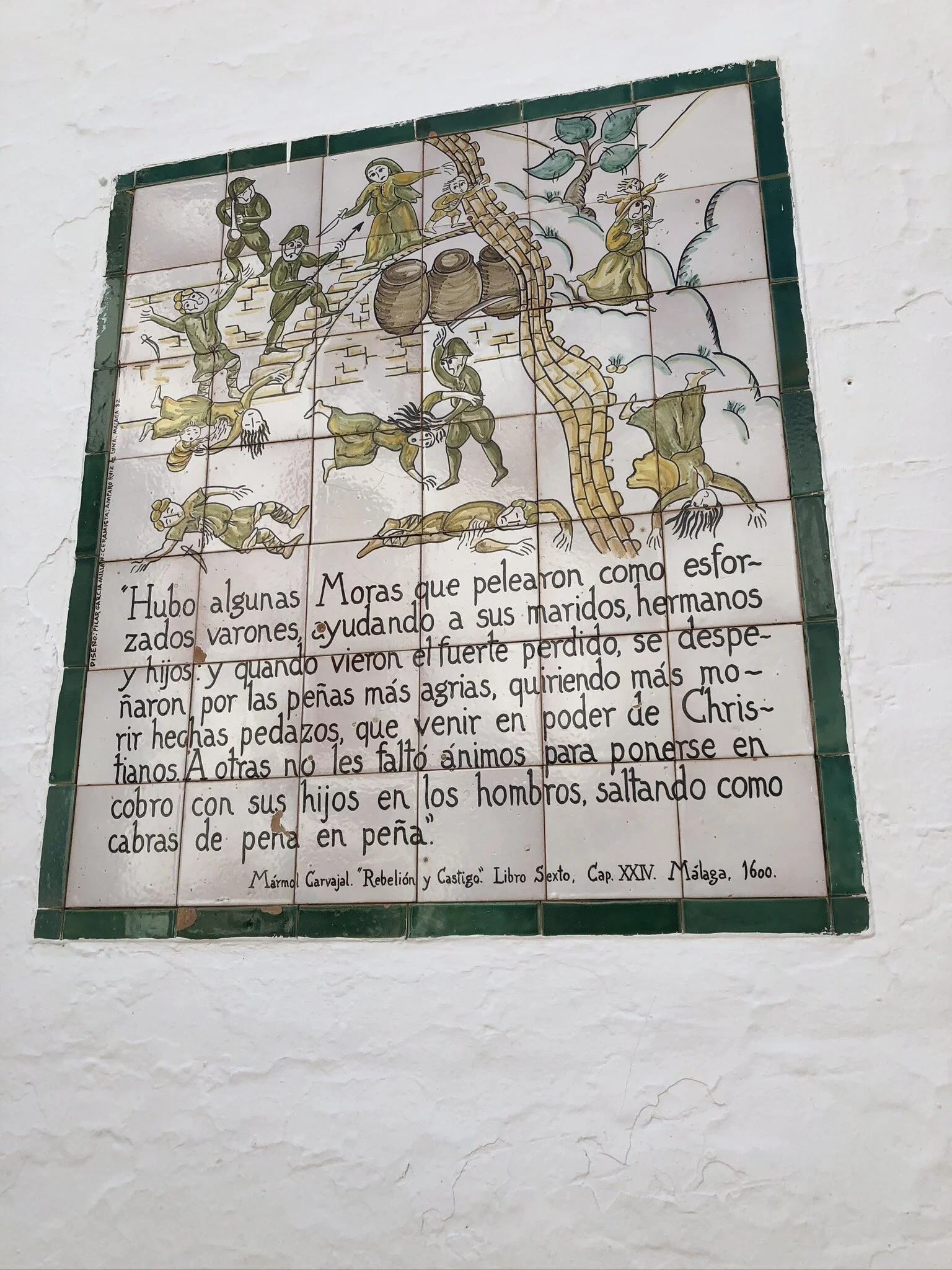

In fact, almost everything that seems so “authentic” about Frigiliana to an outsider now is largely the product of restoration efforts begun relatively recently. The patterned cobblestones replaced dirt and gravel roads only about 50 years ago. The 12 ceramic plaques that guide visitors through the history of the 16th century massacre of the Moors, though they seem ancient, were put in place in 1982, part of a (successful) bid for yet another beautification award. The very blanco of Spain’s most famous pueblo blanco, the whitewashed walls of every home, was only made widespread by a mayoral decree in 1971.

Tourists and foreigners, drawn by the average 320 days of sunshine and the spectacular natural beauty, gradually contributed to a rise in the town’s fortunes. In 1975, the dictator died and a steady stream of Brits began to flee their gloomy isle to vacation and permanently settle in the Costa del Sol, including the awkward twenty year old girl who would one day become my mother.

Perhaps Frigiliana, like Málaga or Nerja, adapted to meet the needs and imaginations of the outsiders; the fantasy of the ‘authentic’ Spanish village, in a way, brought itself into being. Or, more likely, the locals gladly took the foreigners’ money and poured it back into their own community, lovingly resurrecting their battered hometown stone by stone. If it is idealized, it is a Spanish ideal, and has an inner authenticity of its own, whether or not the myriad tourists tramping through year by year (including myself) can fully grasp what it has taken to achieve it.

Standing at the top of the village, clear mountain air in my lungs, gazing down to the Mediterranean, ‘authenticity’ was the last thing on my mind. The more painful your past, the more important it is to find joy in the present moment. Here beauty had been wrestled back from destruction. It didn’t need to be weighed or analyzed to be appreciated.

“We’ve got to get back down,” Casey reminded me, and I glanced at my phone.

“Oh, you’re right. The plane leaves in a few hours.”

“No, no,” he said, “We’ve got to get back to Levi Angelo’s. They sell gelato.”